Neanderthal Man Gets Political

Forget about the Pleistocene. The Neanderthals' greatest evolutionary advance has come in the last decade.

Something strange is happening to Neanderthals. They have been enlisted in the culture wars, where they have emerged as the poster children of misanthropes everywhere.

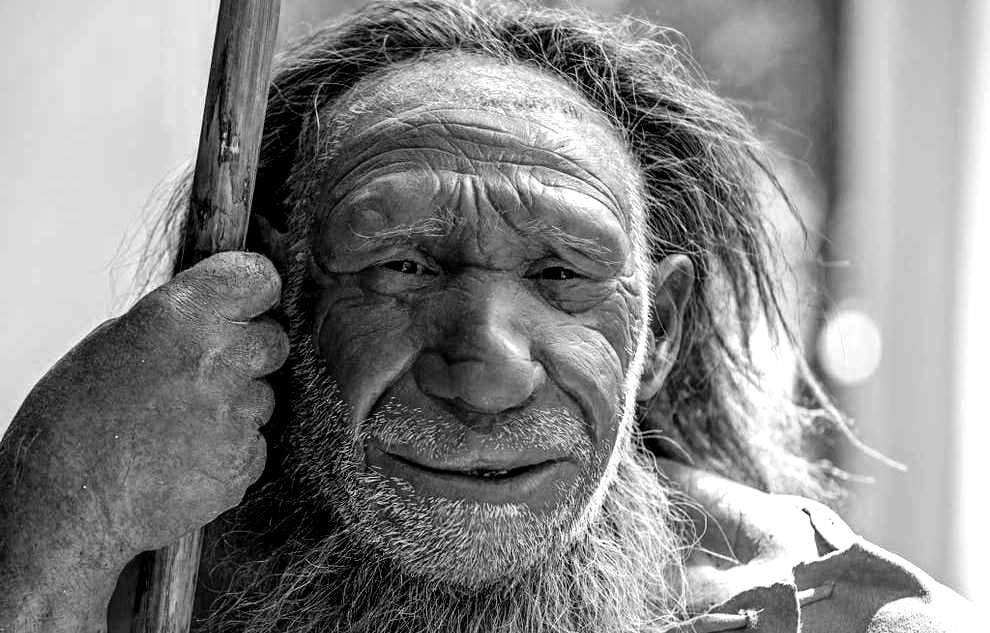

The first Homo neanderthalensis remains were discovered in Germany in the mid-nineteenth century. They revealed a thick-boned, barrel-chested hominid initially thought to be a deformed specimen of homo sapiens. That’s really where the Neanderthals’ identity crisis began, for the Europeans who studied them spent the next century obsessing about their peculiar physiology and the riddle of their “extinction” roughly forty thousand years ago.

Not until 1957, when anthropologists working in Iraq discovered the burial site of ten Neanderthals, did the question of how they might have lived begin to leaven the enduring trope of Neanderthals as dumb, violent brutes. As the veteran anthropologist Erik Trinkaus observed recently, after decades in the field, “those of us studying Neanderthals started thinking about these people in terms of their behavior and not just their anatomy.”

By the end of the twentieth century, the idea of the essential “humanity” of the Neanderthals was ascendant, though not without caveat. Their status as modern humans’ closest evolutionary cousins was acknowledged, and they were imagined to have developed a unique, transmissible culture that included the use of stone tools, the ability to control fire, artistic pursuits like singing and cave painting, and possibly even the medicinal utilization of plants. There remained, however, nagging doubts about Neanderthals’ claims to “full humanity,” including anthropological evidence that their facility for language and symbolic thought were underdeveloped, that they practiced cannibalism and, above all, that they were powerless to forestall their own demise.

But everything changed in 2009, when the Neanderthal genome was sequenced for the first time by Swedish molecular biologist Svante Pääbo and his team. Their great discovery was that every human alive today (save for those whose ancestors never migrated out of Africa) carries roughly two percent Neanderthal DNA, putting paid to the nineteenth-century view that modern humans and Neanderthals were different species and affirming instead that they interbred.

This discovery reinforced the radical hypothesis that there were no salient cognitive differences between modern humans and Neanderthals. In May 2014, a team of researchers from Leiden University and the University of Colorado claimed to have found “no evidence of humans having superior intellect.” One member of the team added that “the stereotype of the primitive Neanderthal is now gradually eroding, at least in scientific circles.”

By 2014, the world was abuzz with Pääbo’s revelations about modern humans’ genetic inheritance from Neanderthals—much of it reported by breathless science popularizers for whom this apparently incontrovertible proof of the Neanderthals’ humanity opened up new vistas for stylish misanthropy.

Such reportage tapped well-rehearsed dystopian narratives about the murderous, self-destructive hubris of modern humans, as well as emergent twenty-first-century narratives about racism and colonialism. The popular story of the maligned and misunderstood Neanderthals increasingly took the form of a redemption narrative. Its main objective was to put modern humans squarely in their place. This meant framing “our” abysmal treatment of Neanderthals—in both the Pleistocene and later the Victorian eras—in the twenty-first-century language of systemic oppression.

In January 2017, the New York Times ran a lengthy feature under the headline “Neanderthals Were People, Too.” It laid out the precepts of the new paradigm:

There is a worldview … that sees our planet as a product of only tumult and indifference. In such a world, it’s possible for an entire species to be ground into extinction by forces beyond its control and then, 40,000 years later, be dug up and made to endure an additional century and a half of bad luck and abuse. That’s what happened to the Neanderthals. And it’s what we did to them. But recently, after we’d snickered over their skulls for so long, it stopped being clear who the boneheads were.

Among the many scientists indicted by the Times for holding abjectly racist views was the British geologist William King, who in 1864 gave Homo neanderthalensis its scientific name. King was dismissed in the Times as a retrograde Victorian snob pursuing pseudo-science:

Who was Neanderthal Man? King felt obligated to describe him. But with no established techniques for interpreting archaeological material like the skull, he fell back on racism and phrenology. He focused on the peculiarities of the Neanderthal’s skull, including the “enormously projecting brow.” No living humans had skeletal features remotely like these, but King was under the impression that the skulls of contemporary African and Australian aboriginals resembled the Neanderthals’ more than “ordinary” white-people skulls. So extrapolating from his low opinion of what he called these “savage” races, he explained that the Neanderthal’s skull alone was proof of its moral “darkness” and stupidity.

To cement the axiom that “we” had treated “them” miserably, the Times quoted an unnamed archaeologist who referred to his more cautious disciplinary peers as “modern human supremacists.”

In early 2018, with Donald Trump in the White House and the perennial congressional debate over Americans’ right to health care in full flame, speculation on Neanderthal social structures was enlisted in the cause of establishing, as one Salon writer put it, that “organized, knowledgeable and caring healthcare is not unique to our species.” The inspiration for this oft-repeated claim was a University of York study of the remains of a Neanderthal male who had suffered from hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy. To endure with this degenerative condition would have required “dedicated care, including monitoring, massage, manipulation and repositioning, fever management, and hygiene maintenance,” according to Salon.

Thereafter, the assumption that Neanderthal “healthcare practices” were driven by the “necessity of a life that was unusually harsh” was supplanted by a rather more progressive scenario, in which “medical care was an integral part of Neanderthals’ lives, and the motivation to take care of each other was likely driven by compassion and empathy.”

Over the summer of 2018, climate change, too, moved to the centre of the Neanderthal story. There had always been speculation about whether some kind of “environmental catastrophe”—volcanic eruptions, abrupt atmospheric cooling—might have vanquished the Neanderthals before modern humans arrived in Europe en masse. But in typical twenty-first-century style, climate change was grafted deftly onto the “human supremacist” narrative.

In 2018, for example, researchers from the University of Cologne theorized that the disappearance of the Neanderthals coincided with two cold, dry periods that lasted for centuries and likely replaced European forests with grassland. One implication of this study was that modern humans did not conquer or even displace Neanderthals, but instead had the good fortune to simply migrate and occupy their now-vacant environs once the climate became more hospitable. Rick Potts of the Smithsonian Institution called the study “refreshing,” for its reinforcement of the proposition that modern humans were not in any way superior. “Our species didn’t outsmart the Neanderthals,” said Potts. “We simply out-survived them.”

Presumably, Neanderthals would have been limited to two broad survival strategies when faced with sudden-onset climate change: adaptation or migration. In July 2018, a study published in the prestigious journal Nature claimed that Neanderthals living in what is now France had known how to create fire for at least five thousand years before the worst of the cooling periods descended upon them. Other European studies suggested that they’d been in possession of this knowledge for at perhaps 150 thousand years. It is not clear whether their fire-making skills might have worked against their long-term survival, by preventing them from taking seriously the option of migrating beyond the cold zone.

But this question of the Neanderthals’ capacity for adaptation may itself be moot. This is because modern humans’ presumed ability to “out-survive” them took place in a milieu of extensive, multi-generational interbreeding between the two groups.

This was the conclusion of a sensational 2018 study of Neanderthal and modern-human genomes, which used computer modeling to suggest that “multiple, independent episodes of interbreeding” took place over many generations. Such modeling sought to explain why, “compared to people with European ancestry, the proportion of Neanderthal DNA is 12 to 20 percent higher in people with East Asian ancestry.” Suddenly, ordinary people availing themselves of commercial DNA testing services wondered what it really meant to carry a disproportionately large number of Neanderthal genes. So did certain government leaders. As Temple University population geneticist Joshua Schraiber put it, rather delicately, “There's been a lot of debate as to why East Asians seem to have a bit more Neanderthal ancestry than Europeans.”

Media coverage of this interbreeding scenario was by and large enthusiastic, for it appeared to shore up the essential humanity—and indeed the sexuality—of Neanderthals. “Neanderthals and Humans Were No One Night Stand,” shouted one typical headline. “Neanderthals and Humans Were Hooking Up Way More Than Anyone Thought,” said another. The implication was obvious. Modern humans carry Neanderthal DNA because, as one report put it, their ancestors “frolicked with these ancient hominins during their migrations.” Even National Geographic speculated that “perhaps our ancestors made love, not war, with their European cousins.”

Peacenik sentimentality aside, Neanderthals would not have emerged from this twenty-first-century redemption narrative as smarter, more empathetic, more socially cohesive, and sexier had it not been wholly imbued with an ethos of presentism—the idea that the contingent past can only be understood meaningfully with reference to the present. As the Canadian curator of a travelling French anthropological exhibit suggested in 2019, it is no longer sufficient to relegate the mysteries of the Neanderthals to prehistory. Rather, we must study them to see “if there are parallels in our own world,” said Janet Young of the Canadian Museum of History. And we must do so “with an open mind.”

Against such relativist constructs, beleaguered antiquarians might offer the rejoinder, Can we not simply let the Neanderthals be Neanderthals?

Apparently not. At the hands of their twenty-first-century popularizers, Neanderthals have evolved into an almost perfectly rendered prehistorical victim group—their bodies denigrated, their culture maligned, their capacity for community and empathy devalued, their medical ethics willfully misconstrued.

And what might the future hold for Neanderthal Man?

In 2011 a researcher at Harvard Medical School charted a detailed biomedical methodology via which Neanderthals might be brought back to life—at the eminently reasonable cost of $30-million for the first iteration. In a world where Western scientists are actively working to revive the woolly mammoth and create human-monkey chimeras, such a Frankenstein scenario no longer seems even the slightest bit fanciful. But if ever such a project is fully realized, it will arrive packing pathos and no small amount of irony, invoking both the wide-eyed wonder of the Neanderthal revisionists, and the critique of modern-human hubris they have so deftly deployed.

One unanticipated coda in the Neanderthal redemption project arose in November 2020, when researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology discovered that a gene cluster some modern humans inherited from Neanderthals increases the need for ventilators in Covid-19 patients by a factor of three. “It is alarming that a genetic heritage from the Neanderthals can have such tragic consequences in the current pandemic,” Svante Pääbo lamented.

Score one for the antiquarians.